The global COVID-19 pandemic measurably exacerbated and increased Americans’ mental health struggles. In particular, the Asian American mental health has been impacted.

In addition to COVID-related trauma from isolation, sickness, death, and grief, the rise of anti-Asian racism and violence during the pandemic has added to the sense of urgency around Asian mental health.

“Many, many Asian Americans are struggling psychologically.” -Dr. Sumie Okazaki, Ph.D.

Stop AAPI Hate, a nonprofit organization that formed during the pandemic to track anti-Asian hate incidents, reported 3,795 incidents of AAPI discrimination, harassment, and physical assault in the U.S. between March 2020 and February 2021.

In fact, during March 2021 the Asian American Psychological Association (AAPA) presented written testimony to the U.S. House of Representatives addressing the impact of racism and violence on Asian mental health during the COVID pandemic.

41% of Asian Americans are experiencing anxiety or depression symptoms.

“Many, many Asian Americans are struggling psychologically,” says Dr. Sumie Okazaki, Ph.D., a researcher and professor of applied psychology who examines the impact of immigration, social change, and race.

“I think the best evidence about the state of Asian American mental health comes from the AAPI COVID-19 needs assessment project directed by Dr. Anne Saw, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Psychology at DePaul University,” Okazaki says. “Their data shows over 40% of Asian American adults are experiencing mental health symptoms.”

According to the assessment project’s report, 41% of Asian Americans are experiencing anxiety or depression symptoms, and—for more than half of Americans who define as Asian—mental health concerns are a significant cause of stress.

How do Asian Americans view mental health support, therapy, and counseling?

What’s more, the report found that 62% of Asian Americans with diagnosed mental health conditions need help accessing care.

So, is there Asian-focused therapy? And how do Asian Americans view mental health support, therapy, and counseling? Read on, to find out more.

Plus, to help address this and connect people to options for care, we’re highlighting resources and tips for finding Asian American therapists, Asian counselors, and psychologists as well as therapists who specialize in multicultural concerns.

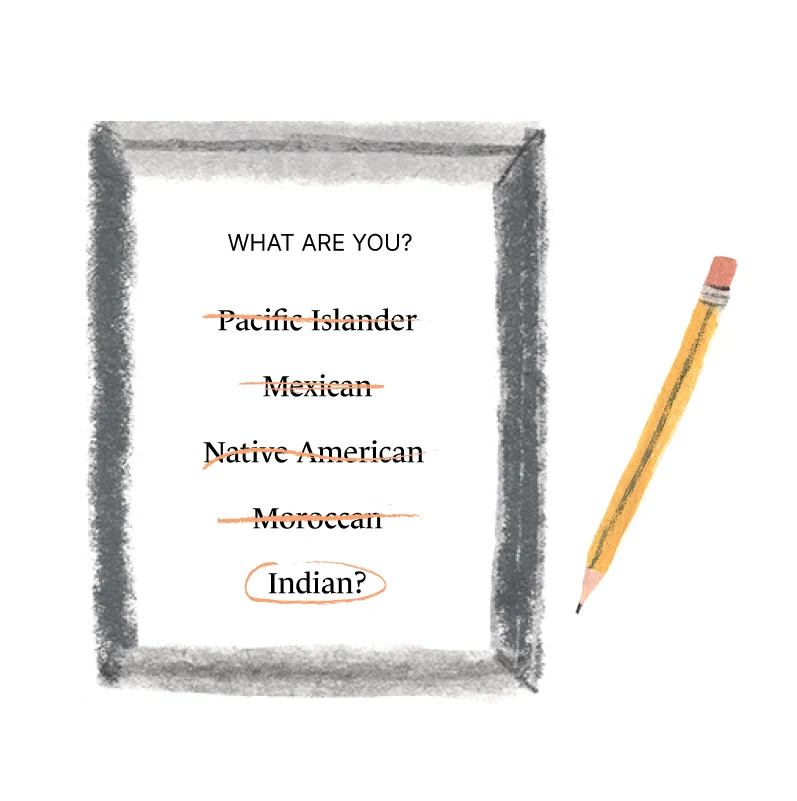

How do you define Asian American, and why is the term controversial?

The term “Asian American” was first used in 1968 by University of California, Berkeley graduate students Chinese American Emma Gee and Japanese American Yuji Ichioka who named their student organization the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA).

Today the terms Asian American or AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) are used as umbrella categories to describe all people whose ancestors are from Asia.

As of 2020 census data, 24 million people in the U.S. identify as Asian American or Pacific Islander.

And, according to a Pew Research Center analysis, Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S.

The Census Bureau defines Asian as “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent.”

Today the terms Asian American or AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) are used as umbrella categories to describe all people whose ancestors are from Asia.

With a population of over 4 billion people (60% of the people on Earth) and a size of 17 million square miles (30% of Earth’s total land mass), Asia is the largest continent in the world, encompassing numerous different cultures.

Consequently, it stands to reason that within the AAPI community, there are also many cultures, ethnicities, and sub-cultures with their own languages, mental health taboos, and specific historic traumas.

In his 2021 book The Loneliest Americans, journalist Jay Caspian Kang argues that grouping all Asian Americans together under this category causes it to become meaningless and incoherent.

Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S.

While they are all considered Asian Americans, there are distinct cultural differences between people of Vietnamese, Japanese, Filipino, Indian, and Pakistani heritage.

In the fall of 2021, Pew Research Center undertook the largest focus group study it had ever conducted–264 total participants from 18 distinct Asian ethnic origin groups–to learn how Asian Americans described their lived experiences in America.

The 18 Asian ethnic groups included in the Pew Research Center study were:

Bangladeshi

Bhutanese

Burmese

Cambodian

Chinese

Filipino

Hmong

Indian

Indonesian

Japanese

Korean

Laotian

Nepalese

Pakistani

Sri Lankan

Taiwanese

Thai

Vietnamese

According to the article about the Pew focus group, many study participants reported that neither “Asian” nor “Asian American” truly captures how they view their identity because these labels are “too broad” or “too ambiguous,” due to so many different groups included within these labels.

Asian American immigrants’ trauma, PTSD, and marginalization

Due to the circumstances and timing for their migration to the U.S. in the mid-1970s, Southeast Asian refugees' lower socioeconomic status contrasted starkly with the “model minority” stereotype that had been created to describe the Asians living in America prior to the 1970s, who were predominantly people of Chinese and Japanese descent.

The Vietnamese, Cambodian, Lao, and Hmong immigrants who arrived in America in the mid-1970s fled extreme war and violence in their home countries.

Cambodian refugees were exposed to extreme trauma before migrating to America to escape the violent persecution by the Khmer Rouge Communists under Pol Pot.

While they are all considered Asian Americans, there are distinct cultural differences between people of Vietnamese, Japanese, Filipino, Indian, and Pakistani heritage.

From 1975-1979 (during Pol Pot's regime), between 1-3 million of the 7 million people in Cambodia died through starvation, disease, or mass executions.

These traumas as well as the stressors associated with relocation, continue to affect the emotional and mental health of many Cambodian refugees and other immigrants.

As the Office of Minority Health (OMH) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) points out, Southeast Asian refugees are particularly at risk for PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) associated with trauma experienced before and after immigration to the U.S.

A study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry found 70% of Southeast Asian refugees receiving mental health care were diagnosed with PTSD.

In a 2003 Connecticut health survey—self-reported depression rates among Vietnamese, Laotian, and Cambodian Americans were 36%, 16%, and 74%, respectively.

A study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry found 70% of Southeast Asian refugees receiving mental health care were diagnosed with PTSD.

In his widely acclaimed 2019 debut novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Vietnamese American author Ocean Vuong creates a shattering portrait of a son composing a letter to his illiterate Vietnamese immigrant mother that explores how traumas of extreme economic hardship and violent generational wounds specific to Vietnamese colonial and personal histories can be passed down through generations.

Those AAPI people who don't fit the East Asian American experience—such as South Asians, Southeast Asians, and Filipinos—report that their experience is overlooked.

An immigrant Nepalese American described in the Pew Research report that “Asian” often means “Chinese” to many Americans.

According to Kevin L Nadal’s 2020 article published in Asian American Policy Review, Filipino Americans, South Asian Americans, and Southeast Asian Americans have called attention to their experiences of marginalization and exclusion.

In particular, Filipino Americans have described discrimination from other Asian Americans, including being told they are “not Asian enough,” according to a 2012 paper on “Racial microaggressions and the Filipino American experience: Recommendations for counseling and development.”

The current state of Asian American mental health

The National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) found Asian Americans have a 17% overall lifetime rate of experiencing any psychiatric disorder.

Mental health research, including this 2018 study, has shown that Asian American children and and young adults have higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts than their White American counterparts.

By some estimates, Asian Americans are three times less likely to seek mental health services than White Americans.

Another 2004 study concluded that Asian American adolescents are more likely to suffer from depressed mood and self-injury risk than White children in the same age range.

However, Black and Asian American adolescents were found especially prone not to ask for help—with the problem especially apparent among Black and Asian American males.

How many Asian Americans go to therapy?

So, are Asian Americans seeking mental health support?

And, importantly, does the current community of medical and mental health professionals offer Asian Americans adequate access to mental health resources and support?

By some estimates, Asian Americans are three times less likely to seek mental health services than White Americans.

A 2007 study found that 9% of Asian Americans sought help for their mental health, which is significantly lower than the U.S. overall average of 18%.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) used 2008-2012 data and found Asian Americans had the lowest estimates of past year mental health service use at 5%—compared to 17% of White Americans, 16% of Native Americans, and 9% of Black Americans.

A 2007 study found that 9% of Asian Americans sought help for their mental health, which is significantly lower than the U.S. overall average of 18%.

And according to a study published in 2018 using data from the Asian American Quality of Life survey, 5% of the Asian Americans surveyed sought help from a mental health specialist.

Why is mental health taboo among Asian Americans?

There are a variety of factors that may contribute to the low percentage of AAPI individuals seeking mental health services, however two significant factors are the taboo, or stigma, around mental health among Asian Americans and the lack of access to adequate resources.

In general, mental health is still taboo across the different Asian American subcultures, according to Dr. Okazaki.

“This may be due to a cultural belief that talking and thinking about negative things can make the situation worse, or a perception that talking about mental health means you are ’weak’ (and potentially a ‘failure’ and may bring shame to yourself and to your family),” she says. “Or, it could be due to simply not knowing how to talk about mental health issues.”

Dr. Han Ren, Ph.D, a psychologist and educator specializing in anxiety, perfectionism, Asian-Americans, and children of immigrants, explains that therapy and counseling are particularly stigmatized among Asian American elder generations who prioritize self-preservation over mental health.

In general, mental health is still taboo across the different Asian American subcultures, according to Dr. Okazaki.

“It also relates with the amount of systemic trauma that our elders have experienced,” says Dr. Ren. “For them, if they have safety and food and shelter—that’s pretty good. To even begin exploring mental health was historically a privilege, so it’s not a priority.”

The narrative around mental health may be shifting as younger Asian Americans advocate for mental health treatment.

“As the next generation ages, Gen Z especially, there’s a lot more acceptance and open discussion around mental health and psychology and psychiatry,” says Dr. Ren.

“There’s almost a compensation or making up for the lost time in the younger Asian Americans I see,” she says. “Because they’ve grown up with this feeling of taboo and lack when it comes to addressing mental health issues.”

Barriers between Asian Americans and therapy

Finding mental health support can often be challenging for Asian Americans since there are multiple hurdles to get across.

Language

Mental Health America (MHA) points out that language barriers may contribute to Asian Americans’ difficulty finding healthcare and other services. 2019 stats from OMH show 31% of Asian Americans do not speak English fluently and in 2019, 74% of AAPI individuals spoke a language other than English at home.

Lack of Asian therapists and psychologists

“There is a direct shortage of culturally capable (for instance, bilingual and bicultural) mental health professionals,” says Dr. Okazaki. “And access is even more limited for those without health insurance or other financial resources.”

It can create additional challenges when an Asian American sees a therapist who may not understand the nuanced values and structures of their culture.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA) Demographics of the U.S. Psychology Workforce data, in 2020 only 3% of American psychologists identified as Asian (as compared to 4% of Black psychologists, 6% of Hispanic psychologists, and 84% of White psychologists).

It can create additional challenges when an Asian American sees a therapist who may not understand the nuanced values and structures of their culture.

Dr. Ren emphasizes the importance of finding a therapist or mental health clinician who is “versed enough in our culture to be able to understand the collectivistic element of Asian family systems and how we often live in communal multi-generational households.”

According to Dr. Ren, “Oftentimes Western therapists and psychologists may advise their clients to cut themselves off from parents without understanding the core value of filial piety in many Asian cultures.”

Financial barriers

On top of all this, it may be surprising to learn that finances and the burden of finding affordable therapy and mental health support can be a very real barrier for Asian Americans.

The “model minority” stereotype and popular culture phenomena, such as Singapore-born Kevin Kwan’s bestselling 2013 novel Crazy Rich Asians (as well as the 2018 film based on Kwan’s book, which was the highest-grossing romantic comedy of the last 10 years), can generalize Asian Americans as having high levels of success and financial stability.

However, in reality, a 2018 Pew Research Center analysis shows Asian Americans are currently the most economically divided major U.S. racial and ethnic group.

According to government data analyzed by Pew Research Center, U.S. income inequality is greatest among Asians. While Asians overall rank as the highest earning racial and ethnic group in America, high income is not a status shared by all Asian Americans.

Between 1970 to 2016, the gap in the standard of living between Asians near the top and the bottom of the income ladder nearly doubled.

Consequently, the top 10% of Asians earn 10 times more than the bottom 10%.

Additionally, as of 2018 U.S. government data, 7% of Asian Americans and 9% of Pacific Islanders do not have health insurance.

“Being able to afford therapy is a big factor, just as it is for pretty much everyone,” says Dr. Ren.

“And when you have the additional barriers such as taboo or not understanding how therapy works or what kind of benefits counseling might offer you—even if you do have financial means—you may not want to spend the money on therapy because there is that barrier of understanding,” she explains.

The importance of Asian American therapists

With so much emphasis on the need for culturally-adept therapists, is it essential for an Asian American to find a therapist who is also Asian American?

Dr. Okazaki explains that this can be especially important if an Asian American client is grappling with racial issues such as microaggressions, the stresses of being an Asian immigrant and/or issues related to being a child of Asian immigrant parents.

“In these cases, having an Asian American therapist can be especially helpful because there may be a shared understanding of what those lived experiences are,” says Dr. Okazaki. “But, of course, just because someone is Asian American doesn't make them a skillful therapist.”

The second thing to take into consideration is the number and availability of Asian American therapists.

“Although the recently added option of video counseling and psychotherapy have eased some access issues, there are still more Asian American clients seeking Asian American therapists than there seem to be available,” says Dr. Okazaki.

Dr. Ren points out that Asian Americans can get great clinical care from a therapist with a different racial or ethnic identity.

However, she acknowledges that seeing a therapist who understands a client’s lived experience can make the therapy experience easier for the client.

“Any time we can see someone who shares certain elements or degrees of our lived experience, we don’t have to explain as much,” says Dr. Ren. “We have someone who can understand the cultural nuance without us having to do that legwork and teaching them.”

She points out we all carry a multitude of demographic intersectionalities in our identities.

“This can be around race,” Dr. Ren explains. “This can be around sexuality, gender identity, class, different types of upbringing and socialization.”

If you are unable to find an Asian therapist near you from your own cultural background, you might consider seeking out a therapist who specializes in multicultural concerns.

7 questions to ask your therapist to ensure they're sensitive to your background and needs

In addition to the general questions to ask any therapist, to help you find a counselor aligned with your specific needs, here are some questions you can ask your therapist (of any background) to determine whether they are sensitive to your cultural background as an Asian American.

Remember, it’s completely valid to ask your therapist these questions, and in no way should you feel bad for asking them.

It’s essential for you to find a counselor or therapist who is the best fit for you.

Have you ever had a patient with my background?

Are you knowledgeable about my culture and are you aware of any biases or misconceptions you may have about it that could affect my treatment from you?

How have you handled clients that have had issues with racism, discrimination, homophobia, or religion?

Are you uncomfortable speaking about matters concerning race, sexuality, identity, or suicide?

Are you open to feedback?

What type of therapy do you provide?

What insurance do you accept? What are your payment plans?

Ready to find a therapist? The Monarch Directory by SimplePractice has over 100,000 and mental health professionals, hailing from a wide variety of cultural and ethnic backgrounds, with approaches and specialties including multicultural concerns.

How to find an Asian American therapist who specializes in AAPI concerns

The Monarch Directory by SimplePractice makes it easy to find a therapist near you who is accepting new clients.

Choose to view therapists by specialty (including therapists near you who specialize in multicultural concerns).

Additionally, find therapists who accept your health insurance plan or therapists offering telehealth video appointments and 15-minute free initial consultations.

On Monarch, you can view therapists’ availability and request an appointment online, often without ever having to pick up the phone.

If you want to find a therapist who specializes in multicultural concerns or who offers a multicultural treatment approach, you can enter your location and filter “By Specialty” and “Approach” to narrow down your selections from there.

For example, if you’re looking for an Asian American therapist in LA, you can view all the therapists in Los Angeles and choose a mental health practitioner such as therapist Angeline Hsu, LMFT, clinical psychologist Dr. Sandra Alfaro Beltran, Psy.D., Filipina social worker Carla Brizuela, LCSW, therapist Lillian Lai, LCSW, who speaks Cantonese, and others.

Or, if you’re looking for an Asian American therapist in New York and New Jersey, you can view all the therapists in NYC and choose licensed clinical therapist Dr. Rowena Talusan-Dunn, LCAT, therapist Puja Trivedi Parikh, LCSW, owner of Pivotal Psychotherapy Services, and Biyang Wang, LCSW, and others.

Mental health resources for Asian Americans

For those who are seeking help with their mental health, there are many online resources as well as forms of community-based support.

If reaching out for help from a mental health professional feels completely out of reach or inaccessible, Dr. Ren points out the importance of prioritizing community, interpersonal connection, and self-care routines that support mental health.

“Other ways to heal include movement, energy healing, community-based healing, and peer support,” she explains.

“Anytime we can experience being seen, understood, and accepted by others, that, in and of itself, is very healing,” says Dr. Ren. “Creating community webs that support that interaction can allow us to access healing in lots of different ways even outside of therapy.”

Subtle Asian Mental Health - This private Facebook group created by the Asian Mental Health Collective has more than 60,000 members and provides a free forum for Asian mental health conversations, connection, and support.

The ABCDesi Support Group - This Sub-Reddit with over 1,400 members is focused on addressing mental health issues within the Desi community. Civil discussions and solutions are shared in a safe space without the fear of judgment.

South Asian Mental Health Initiative and Network (SAMHIN) - This mental wellness support group is for South Asian young adults, ages 16-25. It offers a supportive, nonjudgmental, and confidential space for participants to discuss their experiences related to mental health, stigma, bi-cultural identity, life challenges, stress, and more. The group is run by two facilitators in their 20s and 30s.

“If you’re struggling with suicidal ideation or other thoughts of harming yourself, or if you are having serious symptoms that are interfering with your daily life, it is important to seek help right away,” says Dr. Okazaki. “It takes courage to seek help, but acknowledging and getting help is a sign of strength rather than a sign of weakness.”

To reach the National Suicide Prevention Hotline, call 800-273-8255 or dial 988.

READ NEXT: South Asian Mental Health and Therapy Taboos

Need to find a therapist near you? Check out the Monarch Directory by SimplePractice to find licensed mental health therapists with availability and online booking.