Acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT, is one of the youngest forms of therapy today, but in some ways, it’s also been practiced for centuries. Zen Buddhism, of which acceptance and detachment are essential principles, has been around since the sixth century.

More recently, (and perhaps more familiarly), the Serenity Prayer was written in the 1930s and was popularized thanks to its ubiquity in twelve-step programs.

What is acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in mental health?

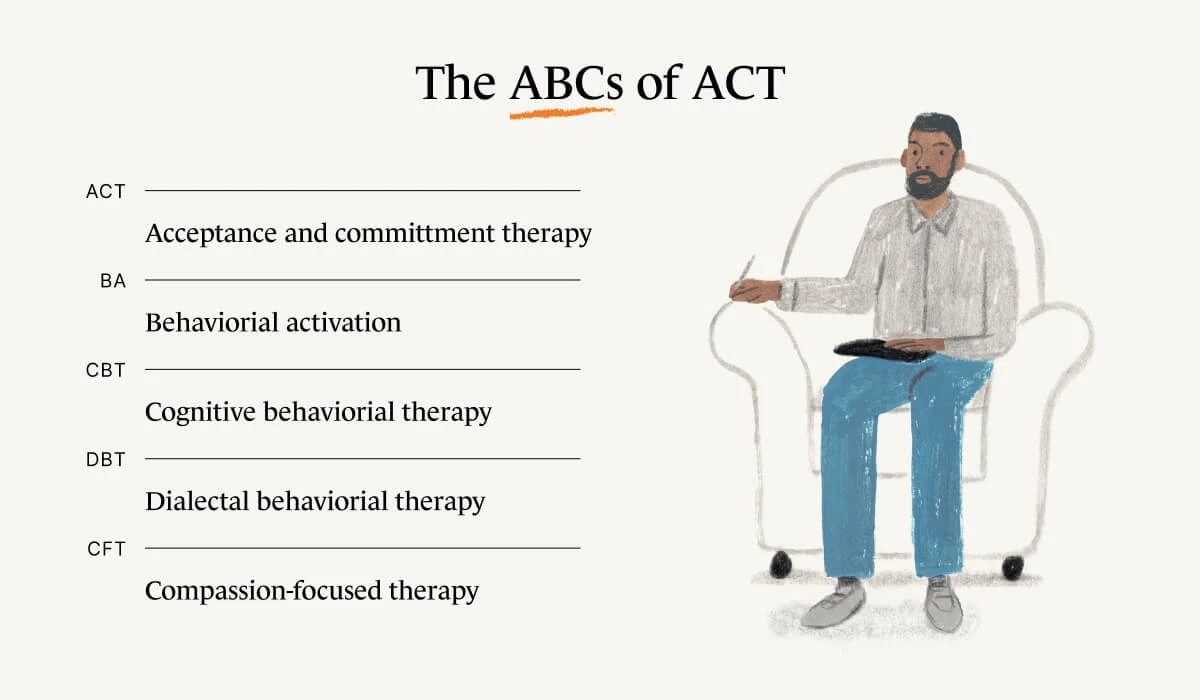

Psychologist Steven C. Hayes developed ACT in the 1980s—but it’s important to note that it is under the umbrella of talk therapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

According to Dr. Nikki Rubin, PsyD, who specializes in ACT, all CBT therapies are evidence-based and share the following characteristics:

They aim to shape/change behavior towards more adaptability/workability (i.e. be able to effectively respond to different situations in adaptive ways)

They increase psychological flexibility (which has been proven to be correlated with psychological well-being)

They aim to help individuals see the world accurately/realistically

They help regulate emotions

ACT in particular emphasizes observing negative thoughts, feelings, or impulses without trying to “fix” them.

Other forms of CBT include dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), behavioral activation (BA), compassion-focused therapy (CFT), among several more.

What’s the difference between ACT and CBT?

The difference is simply that CBT is a family of therapies—one of which is ACT. All CBTs use behavioral science; ACT uses behavioral science in concert with mindfulness to “help build the lives we want even in the presence of pain,” says Dr. Rubin.

This is where we can see echoes of Zen Buddhism: both philosophies accept and even embrace the fact that pain is a necessary part of living.

As Dr. Rubin puts it, “Most times when we are experiencing pain or discomfort, we believe that we must rid ourselves of it before we begin to build the life we want for ourselves. Sadly, we then end up spending our time trying to fix our pain without attending to what gives us meaning, fulfillment, or contentment.”

Part of this acceptance requires the patient to identify their values. Then they can “learn to take steps to engage in behaviors that are aligned with our values—even when we are experiencing pain or discomfort.”

Let’s say treating others with tolerance is valuable to you. With ACT, it would follow that you would practice remaining patient and calm when you’re being yelled at by your neighbor for playing the radio too loud.

How is mindfulness related to ACT?

Mindfulness is very much central to ACT. Dr Rubin says that mindfulness is “the practice of turning the mind back to the present moment and paying attention to and experiencing the present moment as it is.”

If we are unaware, we don’t have the opportunity to recognize our negative feelings for what they are; if we are mindful in the moment of the feeling, we are able to accept that the negative feelings are there—and indeed that negative feelings will crop up from time to time.

“Most times when we are experiencing pain or discomfort, we believe that we must rid ourselves of it before we begin to build the life we want for ourselves. Sadly, we then end up spending our time trying to fix our pain without attending to what gives us meaning, fulfillment, or contentment.”

It’s not easy! Some moments are uncomfortable or unpleasant or downright painful. The natural human impulse is to “engage in behaviors that are aimed at fixing/ridding ourselves of discomfort as opposed to choosing behaviors that are aligned with our values and what we want our lives to be about,” says Dr. Rubin.

“When we are able to cultivate the ability to experience the moment as it is (even when it is unpleasant), we create space and the opportunity to flexibly choose how we want to behave in the present moment.

The present moment is the only place where we have agency over our own behavior—we can't go back and change the past and we can't control the outcome of the future. We can decide what we do in this moment, including making choices that are aligned with our own values.”

What is ACT therapy used for?

ACT has been used to treat a wide diversity of conditions, including

Depression

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

Addiction and substance abuse

Chronic pain

Because of its relative newness, there is less hard-nosed research on the subject as one might want. But broadly speaking, those feeling stuck, lost, or dominated by emotional stress are good candidates for ACT. Sound familiar? Of course it does.

When it comes down to it, pretty much everyone can benefit from some ACT practice. Dr. Rubin agrees. “We can all benefit from learning how to become more behaviorally and psychologically flexible while simultaneously learning how to clarify what they want their lives to be about and taking steps in those directions.”

Association for Contextual Behavioral Science. (2020). ACT for the public. Retrieved from https://contextualscience.org/act_for_the_public

Hayes, S. C., & Hofmann, S. G. (2017). The third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy and the rise of process-based care. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 245–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20442

Mennin, D. S., Ellard, K. K., Fresco, D. M., & Gross, J. J. (2013). United we stand: emphasizing commonalities across cognitive-behavioral therapies. Behavior Therapy, 44(2), 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.02.004