The first encounter I had with an eating disorder was in the eighth grade. I was in the girls’ bathroom at school, changing into my uniform before a volleyball game.

As I fixed my hair in the mirror above a sink, my best friend emerged from one of the bathroom stalls. She was wiping saliva from her mouth. “I just ate such a huge sandwich and bag of chips,” she said. “I had to throw it up.”

I was confused—I only vomited when I was fairly sick, and I couldn’t understand why anyone would willfully make themselves puke.

I somehow understood that when she said “had to” she didn’t mean she couldn’t physically hold it in her stomach. It was because she couldn’t bear the thought of eating so much. I’d felt the same at times.

I asked her how she did it. “Like this,” she said, as she shoved two fingers down her throat to demonstrate. My face made her laugh. “It’s okay,” she said. “I do it all the time.”

I was confused—I only vomited when I was fairly sick, and I couldn’t understand why anyone would willfully make themselves puke. And especially not on a regular basis. I didn’t know exactly why, but I felt sad for my friend—and that feeling let me know what she was doing wasn’t healthy.

But I didn’t quite know what was wrong about it, just that it felt alarming and strange and sad to me.

At lunch in the schoolyard, we’d both grab at the skin around our middle, and complain about our “beer bellies,” a term we’d heard on TV. Even as we moved on to separate high schools, we stayed in touch, and I knew that she continued to binge and purge.

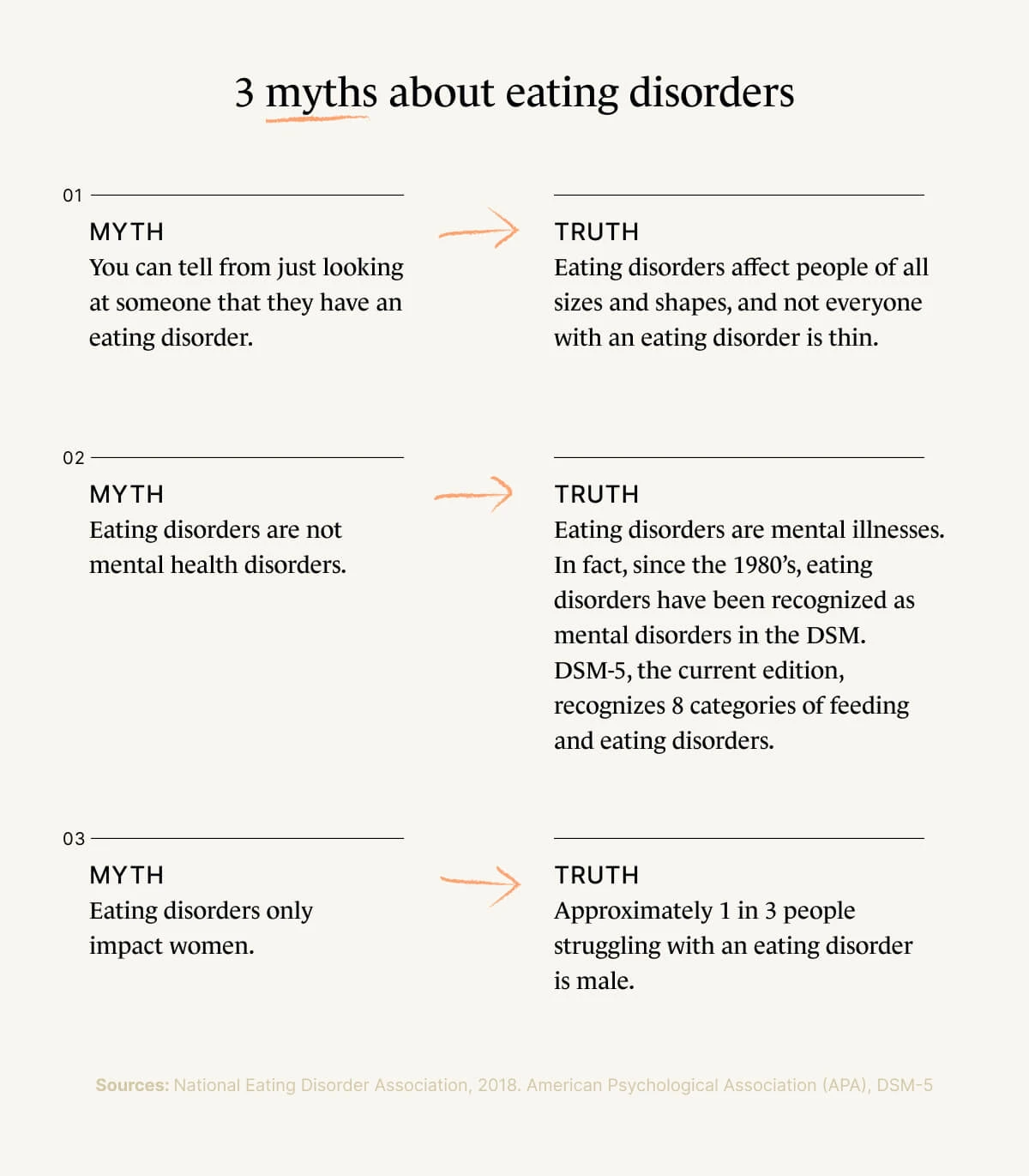

Of course, now I know that eating disorders can affect anyone with any body type.

Everyone who knew her regarded her as “beautiful” and “thin” and I just couldn’t understand why she didn’t see herself that way.*

Years later, at a symposium on women’s health, I attended a session led by a woman who talked about her lifetime battle with anorexia—including multiple brushes with death—and her efforts towards recovery. I remembered my best friend from junior high.

Just like this woman was saying, my friend had often told me that she felt “fat” all the time, despite the fact that at pool parties, one could easily see her hip bones protruding beneath her swimsuit.

Anorexia is the most fatal eating disorder, but bulimia and binge-eating disorder also have grave and potentially life-threatening long-term effects on the body.

Of course, now I know that eating disorders can affect anyone with any body type. Just because a person doesn’t look like your mental image of an eating disorder doesn’t mean they don’t have one. Maladjusted relationships with food strike the skinny, fat, tall, short—there’s no one way an eating disorder looks.

I had heard of anorexia before, and also bulimia. But until I heard that woman talk, I didn’t consider that they were actual illnesses and extremely harmful and potentially fatal ones at that.

Anorexia is the most fatal eating disorder, but bulimia and binge-eating disorder also have grave consequences and potentially life-threatening long-term effects on the body.

Common eating disorder quick facts

Anorexia

According to the Mayo Clinic, the physical signs and symptoms of anorexia nervosa (its formal name) are similar to those of starvation; the most defining symptom of anorexia is severely restricting the amount one consumes. However, a number of emotional and behavioral symptoms are often present, as well, and include:

Preoccupation with food: talking about food, centering social activities around food, even cooking elaborate meals—but not eating them

Adopting rigid rituals around food including using specific flatware or only eating under particular circumstances

Severely restricting food intake through diet or fasting

The Mayo Clinic also states that anorexia includes an “unrealistic perception of body weight and an extremely strong fear of gaining weight or becoming fat.”

Bulimia

Bulimia nervosa (again, technical name) is not limited to the classic binge-and-purge we know from TV. Binging can be more than a big lunch of sandwiches and chips, but a manic frenzy of eating everything in sight. Likewise, purging goes beyond vomiting: Sometimes purging takes the form of extreme exercise or abusing laxatives.

Symptoms of bulimia:

Preoccupation, or constant thinking and talking about weight or body shape

Repeated periods of bingeing, which is eating abnormally large amounts of food at once

A feeling of loss of control while bingeing

Purging after bingeing: This includes forcing oneself to vomit, taking laxatives, extreme exercise, or periods of fasting or highly restrictive dieting

Research suggests that family dynamics play a large part in both the onset of and the recovery from eating disorders. As is true of many young girls, my parents regularly commented on my weight as I was growing up, and would complain I didn’t exercise more or eat less.

This is a common phenomenon, and family pressure can contribute to the onset of an eating disorder. On the other hand, family influence can help someone begin to heal from an eating disorder.

The earlier family members are made aware of their potentially harmful influence on disordered eating, the easier it is to intervene against damaging behaviors and physical side effects.

Are there other eating disorders?

According to the DSM-5, which is the handbook used by healthcare professionals to diagnose mental disorders, eating disorders are illnesses in which people experience severe disturbances in their behaviors around eating, as well as related disturbances in thought and emotions.

Eating disorders affect several million people at any given time, and women between the ages of 12 and 35 are most at risk.

The three most common types of eating disorders are anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. But there are several other ways people have problematic relationships with food, including orthorexia, which is a near-neurotic obsession with healthy food.

It is also worth noting that in many cases, other psychiatric disorders like obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, panic, and alcohol and drug abuse problems occur together with eating disorders. Indeed, these behavioral disorders can exacerbate each other.

Do men get eating disorders?

Statistically, about 9% of all people suffer from an eating disorder at some point in their lifetime; one in three is likely to be male.

Many of the behaviors typical of an eating disorder such as binge-eating, purging, and fasting for weight loss, are nearly as common in men as they are in women, even if they are not repeated with enough regularity to qualify for a clinical diagnosis.

That said, his behavior shows how disordered eating and worrying about weight is not limited to women.

A lot has been said and written about the pressure, both covert and overt, placed on girls and women by a culture that glamorizes thin, young, often white, beauty standards. But just as much could be said for how these same factors adversely affect men and boys.

As a child, I witnessed my father repeatedly raiding our fridge and pantry, eating entire boxes of crackers, then cookies, then packages of bread rolls and butter. Later that day or the next, he’d suddenly disappear on a 50-mile bike ride or 10-mile-run (without having exercised much at all in the preceding weeks).

He also imposed dramatic diets on himself. This included one in which, for several weeks, he ate nothing but tofu pie: a concoction of tofu, pureed in a blender with a few packets of flavored Crystal Light powder and Equal sweetener, poured into a store-bought graham cracker crust.

Sometimes the pie was a pale green if the Crystal Light was lemonade-flavored, other times, pink, for raspberry flavor.

The tofu pie was inedible by anyone else in our household, and maybe the world. But he was willing to go to any extreme to lose weight. He even signed up for and ran a marathon on a whim one weekend, without having run more than a mile in the months prior to race day.

As expected, he could barely walk for a week afterward, but he was quite pleased that he not only finished, he managed to lose several pounds.

These behaviors have hallmarks of both anorexia (extreme caloric restriction) and bulimia (binging and then purging with exercise), but my father’s behaviors were likely also tied to other psychological factors. That said, his behavior shows how disordered eating and worrying about weight is not limited to women.

How do you treat an eating disorder?

With proper medical care, many eating disorders can be treated effectively. Typical treatment involves a combination of talk therapy, education on nutrition and on environmental triggers, and medical monitoring, and sometimes medication for anxiety or other underlying psychological illnesses.

If you think you or a loved one may have an eating disorder, there are a number of options and resources available to help. Talking to your primary care physician is a good place to start. So is talking to a nutritionist or a therapist. Many therapists will list directly in their personal profiles or website if they specialize in treating eating disorders.

National resources include:

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD) lists a number of educational materials, eating disorder support groups, and great articles about eating disorder identification and treatment.

National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) is the largest non-profit organization in the U.S. working to prevent eating disorders. They hosts an online eating disorder screening tool for people ages 13 and up, and also hosts an eating disorder helpline.

Whether your behavior around eating has become disturbed (meaning it interferes with your ability to connect with others or to work or play as usual), seems abnormal, or feels out of control, know that you are not alone and that there is help.

If you are concerned about a loved one’s behavior or well-being and you want support on how to talk to them and possibly intervene, you also are not alone, and will likely benefit from talking to a mental health professional.

Finally, if you’re just not sure about any of the above, keep educating yourself about eating disorders and see what resonates with you. Everyone deserves to have a healthy life and to regard their own body and its own appetites with joy rather than aversion. We all have a part to play in building a culture and societal mindset that makes that possible.

* Quotes are used around these terms as they are subjective as both values and in actuality.

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74

Cerniglia, L., Cimino, S., Tafà, M., Marzilli, E., Ballarotto, G., & Bracaglia, F. (2017). Family profiles in eating disorders: Family functioning and psychopathology. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, Volume 10, 305–312. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s145463

Cowden, S. (2020, November 20). Obsessive-compulsive disorder and eating disorders. Verywell Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-and-eating-disorders-1138191

le Grange, D., Lock, J., Loeb, K., & Nicholls, D. (2010). Academy for Eating Disorders position paper: The role of the family in eating disorders. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(1), 1–5. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20751

Leys, C., Kotsou, I., Goemanne, M., & Fossion, P. (2017). The influence of family dynamics on eating disorders and their consequence on resilience: A mediation model. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 45:2, 123-132, Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2017.1303654

Mayo Clinic. (2018). Anorexia nervosa - Symptoms and causes. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anorexia-nervosa/symptoms-causes/syc-20353591

National Eating Disorders Association. (2017, February 25). Eating disorders in men & boys. Retrieved from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/learn/general-information/research-on-males

Psychiatry.org. (2017). What are eating disorders? Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016, June). Table 20, DSM-IV to DSM-5 Bulimia Nervosa Comparison. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519712/table/ch3.t16/